Expo

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

Clinical Chem.Molecular DiagnosticsHematologyImmunologyMicrobiologyPathologyTechnologyIndustry

Events

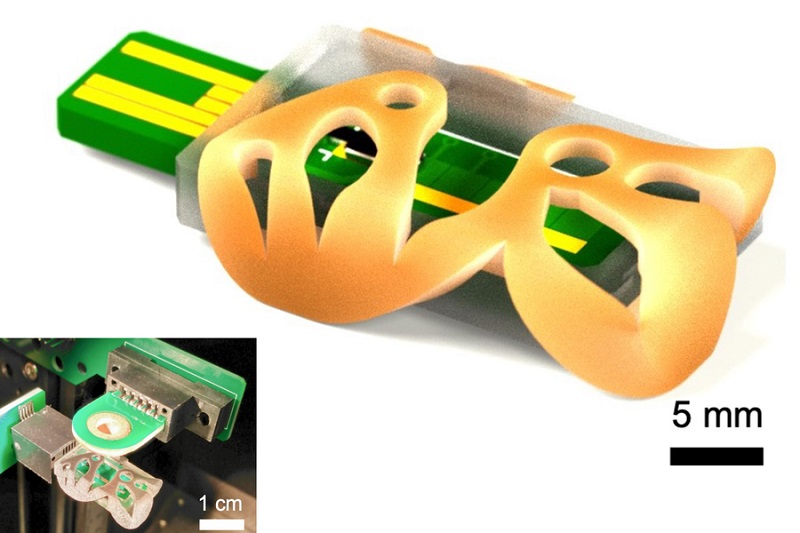

- POC Biomedical Test Spins Water Droplet Using Sound Waves for Cancer Detection

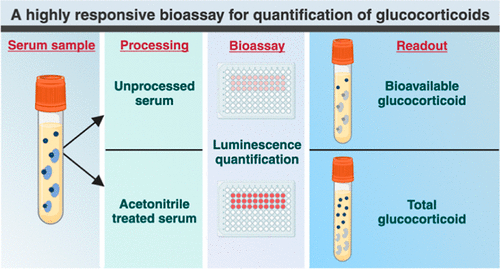

- Highly Reliable Cell-Based Assay Enables Accurate Diagnosis of Endocrine Diseases

- New Blood Testing Method Detects Potent Opioids in Under Three Minutes

- Wireless Hepatitis B Test Kit Completes Screening and Data Collection in One Step

- Pain-Free, Low-Cost, Sensitive, Radiation-Free Device Detects Breast Cancer in Urine

- Unique Autoantibody Signature to Help Diagnose Multiple Sclerosis Years before Symptom Onset

- Blood Test Could Detect HPV-Associated Cancers 10 Years before Clinical Diagnosis

- Low-Cost Point-Of-Care Diagnostic to Expand Access to STI Testing

- 18-Gene Urine Test for Prostate Cancer to Help Avoid Unnecessary Biopsies

- Urine-Based Test Detects Head and Neck Cancer

- First 4-in-1 Nucleic Acid Test for Arbovirus Screening to Reduce Risk of Transfusion-Transmitted Infections

- POC Finger-Prick Blood Test Determines Risk of Neutropenic Sepsis in Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy

- First Affordable and Rapid Test for Beta Thalassemia Demonstrates 99% Diagnostic Accuracy

- Handheld White Blood Cell Tracker to Enable Rapid Testing For Infections

- Smart Palm-size Optofluidic Hematology Analyzer Enables POCT of Patients’ Blood Cells

- AI Tool Precisely Matches Cancer Drugs to Patients Using Information from Each Tumor Cell

- Genetic Testing Combined With Personalized Drug Screening On Tumor Samples to Revolutionize Cancer Treatment

- Testing Method Could Help More Patients Receive Right Cancer Treatment

- Groundbreaking Test Monitors Radiation Therapy Toxicity in Cancer Patients

- State-Of-The Art Techniques to Investigate Immune Response in Deadly Strep A Infections

- Mouth Bacteria Test Could Predict Colon Cancer Progression

- Unique Metabolic Signature Could Enable Sepsis Diagnosis within One Hour of Blood Collection

- Simple Blood Test Combined With Personalized Risk Model Improves Sepsis Diagnosis

- Groundbreaking Diagnostic Platform Provides AST Results With Unprecedented Speed

- Blood Analysis Predicts Sepsis and Organ Failure in Children

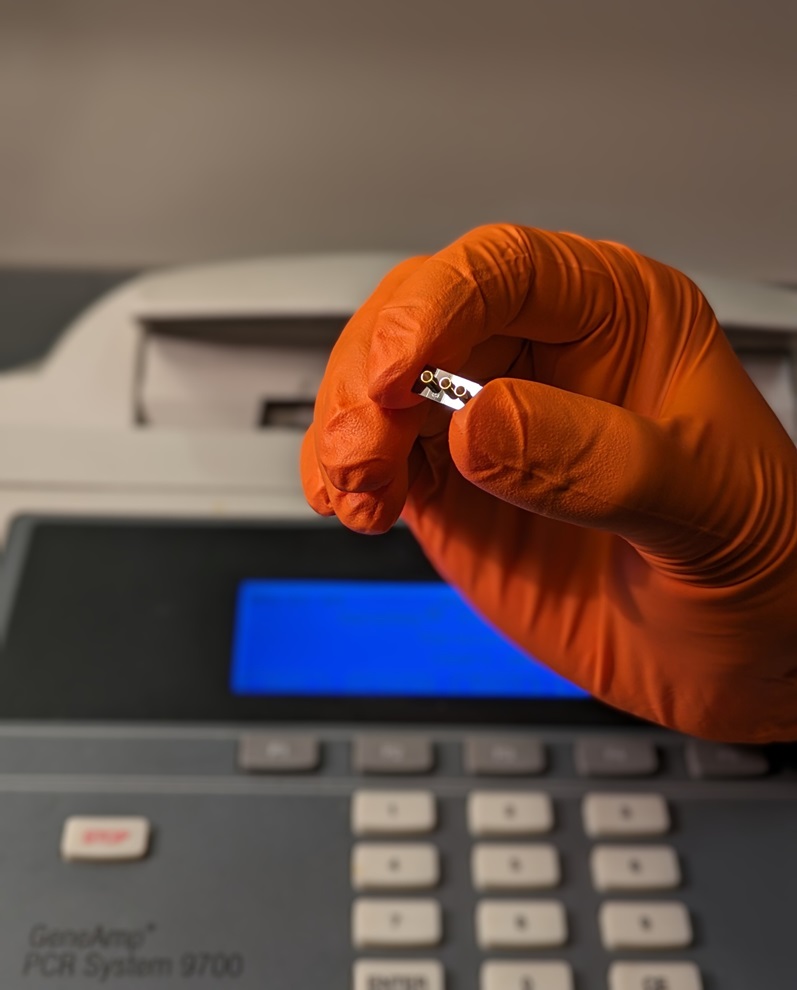

- DNA Biosensor Enables Early Diagnosis of Cervical Cancer

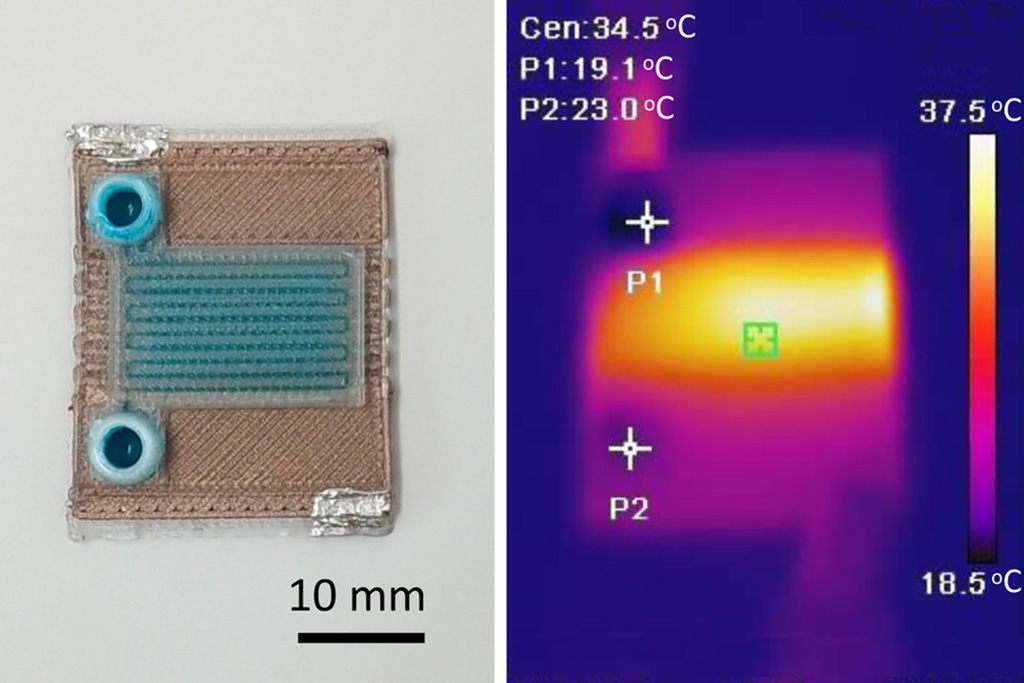

- Self-Heating Microfluidic Devices Can Detect Diseases in Tiny Blood or Fluid Samples

- Breakthrough in Diagnostic Technology Could Make On-The-Spot Testing Widely Accessible

- First of Its Kind Technology Detects Glucose in Human Saliva

- Electrochemical Device Identifies People at Higher Risk for Osteoporosis Using Single Blood Drop

- Bosch and Randox Partner to Make Strategic Investment in Vivalytic Analysis Platform

- Siemens to Close Fast Track Diagnostics Business

- Beckman Coulter and Fujirebio Expand Partnership on Neurodegenerative Disease Diagnostics

- Sysmex and Hitachi Collaborate on Development of New Genetic Testing Systems

- Sysmex and CellaVision Expand Collaboration to Advance Hematology Solutions

- Gene Panel Predicts Disease Progession for Patients with B-cell Lymphoma

- New Method Simplifies Preparation of Tumor Genomic DNA Libraries

- New Tool Developed for Diagnosis of Chronic HBV Infection

- Panel of Genetic Loci Accurately Predicts Risk of Developing Gout

- Disrupted TGFB Signaling Linked to Increased Cancer-Related Bacteria

- New Method Offers Sustainable Approach to Universal Metabolic Cancer Diagnosis

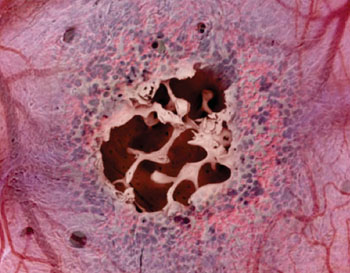

- Spatial Tissue Analysis Identifies Patterns Associated With Ovarian Cancer Relapse

- Unique Hand-Warming Technology Supports High-Quality Fingertip Blood Sample Collection

- Image-Based AI Shows Promise for Parasite Detection in Digitized Stool Samples

- Deep Learning Powered AI Algorithms Improve Skin Cancer Diagnostic Accuracy

Expo

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

Clinical Chem.Molecular DiagnosticsHematologyImmunologyMicrobiologyPathologyTechnologyIndustry

Events

Advertise with Us

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

Clinical Chem.Molecular DiagnosticsHematologyImmunologyMicrobiologyPathologyTechnologyIndustry

Events

Advertise with Us

- POC Biomedical Test Spins Water Droplet Using Sound Waves for Cancer Detection

- Highly Reliable Cell-Based Assay Enables Accurate Diagnosis of Endocrine Diseases

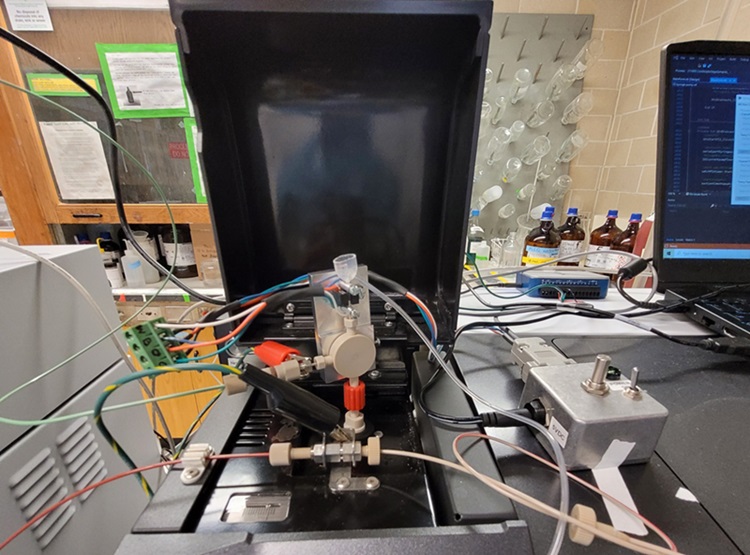

- New Blood Testing Method Detects Potent Opioids in Under Three Minutes

- Wireless Hepatitis B Test Kit Completes Screening and Data Collection in One Step

- Pain-Free, Low-Cost, Sensitive, Radiation-Free Device Detects Breast Cancer in Urine

- Unique Autoantibody Signature to Help Diagnose Multiple Sclerosis Years before Symptom Onset

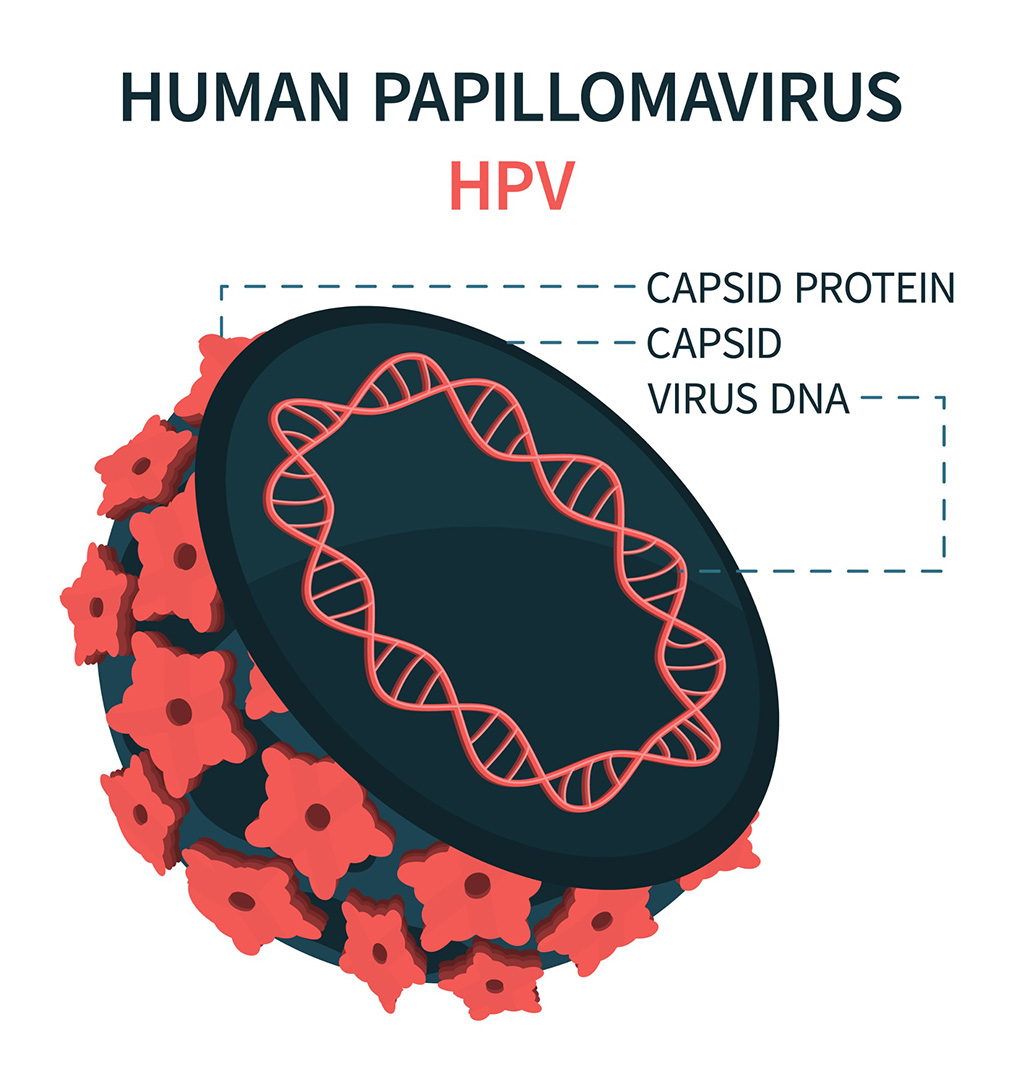

- Blood Test Could Detect HPV-Associated Cancers 10 Years before Clinical Diagnosis

- Low-Cost Point-Of-Care Diagnostic to Expand Access to STI Testing

- 18-Gene Urine Test for Prostate Cancer to Help Avoid Unnecessary Biopsies

- Urine-Based Test Detects Head and Neck Cancer

- First 4-in-1 Nucleic Acid Test for Arbovirus Screening to Reduce Risk of Transfusion-Transmitted Infections

- POC Finger-Prick Blood Test Determines Risk of Neutropenic Sepsis in Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy

- First Affordable and Rapid Test for Beta Thalassemia Demonstrates 99% Diagnostic Accuracy

- Handheld White Blood Cell Tracker to Enable Rapid Testing For Infections

- Smart Palm-size Optofluidic Hematology Analyzer Enables POCT of Patients’ Blood Cells

- AI Tool Precisely Matches Cancer Drugs to Patients Using Information from Each Tumor Cell

- Genetic Testing Combined With Personalized Drug Screening On Tumor Samples to Revolutionize Cancer Treatment

- Testing Method Could Help More Patients Receive Right Cancer Treatment

- Groundbreaking Test Monitors Radiation Therapy Toxicity in Cancer Patients

- State-Of-The Art Techniques to Investigate Immune Response in Deadly Strep A Infections

- Mouth Bacteria Test Could Predict Colon Cancer Progression

- Unique Metabolic Signature Could Enable Sepsis Diagnosis within One Hour of Blood Collection

- Simple Blood Test Combined With Personalized Risk Model Improves Sepsis Diagnosis

- Groundbreaking Diagnostic Platform Provides AST Results With Unprecedented Speed

- Blood Analysis Predicts Sepsis and Organ Failure in Children

- DNA Biosensor Enables Early Diagnosis of Cervical Cancer

- Self-Heating Microfluidic Devices Can Detect Diseases in Tiny Blood or Fluid Samples

- Breakthrough in Diagnostic Technology Could Make On-The-Spot Testing Widely Accessible

- First of Its Kind Technology Detects Glucose in Human Saliva

- Electrochemical Device Identifies People at Higher Risk for Osteoporosis Using Single Blood Drop

- Bosch and Randox Partner to Make Strategic Investment in Vivalytic Analysis Platform

- Siemens to Close Fast Track Diagnostics Business

- Beckman Coulter and Fujirebio Expand Partnership on Neurodegenerative Disease Diagnostics

- Sysmex and Hitachi Collaborate on Development of New Genetic Testing Systems

- Sysmex and CellaVision Expand Collaboration to Advance Hematology Solutions

- Gene Panel Predicts Disease Progession for Patients with B-cell Lymphoma

- New Method Simplifies Preparation of Tumor Genomic DNA Libraries

- New Tool Developed for Diagnosis of Chronic HBV Infection

- Panel of Genetic Loci Accurately Predicts Risk of Developing Gout

- Disrupted TGFB Signaling Linked to Increased Cancer-Related Bacteria

- New Method Offers Sustainable Approach to Universal Metabolic Cancer Diagnosis

- Spatial Tissue Analysis Identifies Patterns Associated With Ovarian Cancer Relapse

- Unique Hand-Warming Technology Supports High-Quality Fingertip Blood Sample Collection

- Image-Based AI Shows Promise for Parasite Detection in Digitized Stool Samples

- Deep Learning Powered AI Algorithms Improve Skin Cancer Diagnostic Accuracy

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)